One of the Most Important Poets of Our Time Has Passed Away

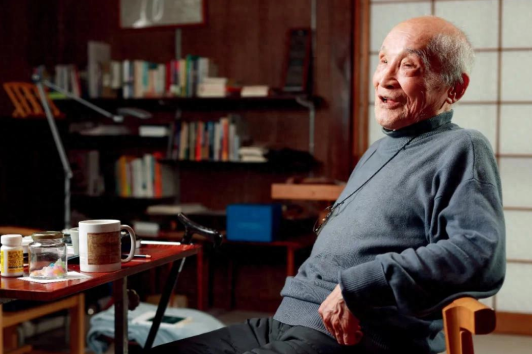

On November 6, 2024, renowned Japanese poet and translator Tanigawa Shuntarō met with his friend and translator Tian Yuan at his home to discuss various matters, as he had done every month for years. As the Chinese translator of Tanigawa’s works, Tian had been closely monitoring his friend’s health. That day, everything appeared normal; a vibrant Tanigawa even shared a newly completed poem titled “Gratitude,” which began with the lines: “Waking up / seeing the red leaves in the yard / thinking of yesterday / it turns out I am still alive.” No one foresaw that this poem would become Tanigawa’s farewell to the world. Just a week later, on November 13, Tanigawa Shuntarō passed away in a hospital in Tokyo at the age of 92.

Chinese readers are no strangers to Tanigawa’s work; his fresh and poignant verses circulate widely on the internet, with famous lines from his masterpieces “Twenty Billion Light-Years of Solitude” and “The End of Spring” frequently recited. Within Japan’s literary circles and worldwide, Tanigawa is regarded as one of the most significant poets of contemporary times. He has been described as “the standard-bearer of modern Japanese poetry,” “the poet of the universe,” and “the people’s poet,” with his works often included in Japanese textbooks. Since publishing his first poetry collection in 1952, he maintained a prolific writing career for 72 years, expressing the states of nature and human life in a refreshing and emotional style that consistently resonates with readers.

In addition to his immense literary influence, Tanigawa Shuntarō was known for his diligence and productivity, having published an astounding 85 original poetry collections throughout his life. He also ventured into other artistic fields, including children’s poetry, pop lyrics, and manga translation. His lyrics for popular animated series such as “Astro Boy” and “Howl’s Moving Castle,” as well as the Japanese version of Charles Schulz’s “Peanuts,” are well-known. This vast body of work, expressed in a variety of styles, has attracted readers from different ages and nationalities, establishing Tanigawa as one of Japan’s most internationally influential poets.

Now, this tirelessly dedicated “poet of the universe” has laid down his pen and quietly drifted into another realm that belongs to him.

The Gentle and Sincere “People’s Poet”

Following Tanigawa’s death, Tian Yuan chose to guard the poet’s body at the funeral home on November 15 and 17, bidding farewell to his close friend. Through tear-filled eyes, he gazed upon Tanigawa’s remains, still unable to accept that this smiling, gentle friend with whom he had shared so much was gone. At one moment, he even fantasized about waking Tanigawa to continue their unfinished conversations.

As the authoritative translator of Tanigawa’s works into Chinese, Tian Yuan has been dedicated to introducing the poet’s works to Chinese readers for many years. Living in Japan, he understands the high regard in which this “people’s poet” is held by the general public. Tanigawa’s simple yet profound verses often appear in the lives of ordinary Japanese people—featured in TV advertisements, printed on beer bottles, or set to music as popular songs. This influence can be witnessed in everyday life. Tian recalled a humorous incident from years ago when he took Chinese poet Bei Dao to visit Tanigawa. Upon getting into a taxi, he mentioned to the driver that they were going to see Tanigawa. The driver turned and said, “Tanigawa Shuntarō, the poet, right?”

Tanigawa’s widespread recognition stems from the fact that his poetry consistently addresses ordinary people and the masses. He enjoyed depicting the sky, trees, nature, and the universe, as well as exploring basic human desires and emotional experiences. His themes are diverse, but no matter how they vary, he always conveys the genuine emotions felt in the moment of writing and accurately describes the state of being “alive.” In fact, one of his representative works is a poem titled “Living,” which states: “Living / what it means to live now / is the barking of a dog in the distance / is the rotation of the Earth right now / is the cry of a new life somewhere / is a soldier wounded in some place / is the swinging of a swing / is the passage of time.”

Such lively and moving poetry arises from the deep honesty of Tanigawa’s character: a complete fidelity to his inner feelings. As a friend, Tian Yuan was deeply impressed by Tanigawa’s candidness. Once, while traveling together, Tian noticed Tanigawa jotting down something in a notebook and inquired. Tanigawa explained that he was writing haikus. When Tian asked to see the poems, Tanigawa immediately declined, stating that he felt his haikus were unworthy because he lacked the proper skills. As a fellow creator, Tian immediately recognized that Tanigawa was not being modest; he was honestly expressing his state—despite being a celebrated poet, he acknowledged his flaws in poetry.

This honesty permeated not only his works but also his actions and interactions, forming a significant part of his personality and poetic appeal. Consequently, his actions often conveyed a sense of unpretentious sincerity. He openly discussed his love for women and his pursuit of romantic freedom as driving forces behind his poetry. He went through three marriages and was still animatedly discussing views on love with young people in his later years, exploring various romantic complexities in his poetry.

Moreover, Tanigawa was an unusual figure among poets, candidly discussing economic interests. He once stated that the most important things in his life, in order, were women, music, poetry, and money. Although he ranked money last, it is rare for a poet to so openly acknowledge the significance of financial matters. He often shared his worries about not having a college diploma and being concerned about his writing career as a means to support his family. A significant part of his motivation to write stemmed from survival anxiety.

It was precisely because of his sincerity that he could crystallize these feelings into fresh phrases, capturing the true state of “being alive” for everyone. As a result, he garnered understanding, empathy, and support from readers worldwide. Statistics indicate that Tanigawa Shuntarō’s poetry has been translated into over twenty languages and published in more than thirty countries, featuring in over eighty foreign editions of poetry collections. “In Japan’s nearly 150 years of modern poetry history, a poet like Tanigawa, read by various age groups and continuously read by people from different eras, is virtually unprecedented,” Tian Yuan remarked to China News Weekly.

A Fortuitous Literary Standard-Bearer

In truth, Tanigawa Shuntarō’s family background predisposed him to becoming a literary figure. His father was the renowned Japanese philosopher and literary theorist Tanigawa Tetsuo, a friend of literary figures such as Kawabata Yasunari and Mishima Yukio. Born in 1931 as the only child, Tanigawa Shuntarō had access to his father’s extensive library and enjoyed the care of his mother and other female relatives, making him a fortunate and happy child.

However, despite his privileged background, Tanigawa did not choose a conventional academic path. He was well-read but disliked the rigidity of school education, even refusing to attend university. During his rebellious teenage years, under the influence of classmates, he began contributing to literary magazines and learned to write poetry. After graduating from junior high school, he attended a kind of night school to obtain a diploma while secretly continuing to write poetry in his notebook. Eventually, on one fateful day at the age of 19, his father discovered some of his poems, recognized his literary talent, and shared them with the Japanese poet Miyao Takashi for evaluation. Miyao praised Tanigawa’s work and recommended it to the prominent literary magazine Bungakkai, leading to a sensational debut. By 1952, Tanigawa’s first poetry collection, “Twenty Billion Light-Years of Solitude,” was published, and he became an overnight sensation at just 21 years of age.

Tanigawa’s entry into the literary world was serendipitous, and his poetic style diverged significantly from the prevailing literary trends in Japan at the time. Tian Yuan noted that during this period, poets associated with the “Aland” school, shaped by war experiences, and the “Archipelago” school, focused on social issues, contrasted sharply with Tanigawa and his friend Ōoka Shōhei, who developed a unique poetic style. They neither depicted the harsh realities of war nor expressed enthusiasm for societal events but concentrated on personal feelings and experiences. Tanigawa’s imaginative expression in his debut work illustrates this individual and pure articulation, exploring themes such as Martians and Earth’s inhabitants becoming friends and the notion that “the universe is tilting, so everyone longs to meet.”

Thus, with his sensitivity and talent, Tanigawa easily gained readers and sales; however, he also endured decades of indifference and neglect from critics. From the moment he began writing poetry until the 1970s, he was overlooked by prestigious literary awards. This bias within Japanese literary circles stemmed largely from the fact that he initially benefited from his father’s influence. Many award judges held a grudge against him, refusing to acknowledge the value of his work. The Japanese literary community has a tradition of “spiritual purity,” and as a result, Tanigawa had to silently bear this discrimination.

Resilient, Tanigawa did not lose heart; instead, this discrimination and his desire for financial stability fueled his creativity. He began accepting numerous assignments from publishers and produced various types of literary works, trying to win over more readers through broader dissemination. Gradually, his poetry was translated into multiple languages, gained popularity overseas, and received recognition from literary circles. However, this process took many years; it was not until 2010, at the age of 79, that Tanigawa received the prestigious “H Prize for Poetry,” one of Japan’s most significant contemporary poetry awards, on par with the celebrated Akutagawa Prize. This award represented a long-overdue acknowledgment from the Japanese literary community.

The “Paper-Eating Sheep” in Search of Exploration

According to the Chinese zodiac, Tanigawa Shuntarō, born in 1931, belongs to the Year of the Sheep. He seemed to have contemplated this symbolism, often referring to himself as a “paper-eating sheep” and describing himself as a craftsman perpetually exploring literature. For years, he diligently explored new content in poetry, seeking to innovate his language and form. The phrase “driven by life” served only as a façade, concealing an exceedingly lofty literary ideal.

Over the decades, Tanigawa’s fresh and accessible poetry has been widely disseminated, yet those familiar with him recognize that he continually evolved his abilities, striving to go further down the path of pure literature. Many are unaware that Tanigawa experimented with satirical poetry in the 1960s and delved into complex surrealism in the 1980s. Tian Yuan noted that Tanigawa’s poetry collections “Coca-Cola Course,” published in 1980, and “Melancholy Flowing Downstream,” published in 1988, along with some obscure prose poetry, are challenging to translate due to their profound meanings and artistic quality. Furthermore, Tanigawa’s poetry also explored novel expressions in the Japanese language. These explorations, which ordinary readers might not recognize, carry invaluable significance in the realm of literature.

Regardless of the changes in his works, Tanigawa consistently maintained a tone that avoided political commentary and refrained from engaging in reality. This stance did not imply indifference to the world; rather, it demonstrated his own beliefs and attitudes that remained unaffected by external influences. After the devastating “3.11” earthquake in Japan in 2011, many media outlets approached him for contributions, hoping he would voice his thoughts on the disaster. He declined and instead donated a sum of money to the Japanese Red Cross. He also turned down honors such as the Prime Minister’s Award and decorations from the Emperor of Japan, preferring to abstain from engaging more with reality. Although he seldom discussed social issues, he occasionally embedded his pursuit of love and peace while opposing violence and conflict within his verses. As he wrote in his satirical poem “Who is It?”: “Who kills? The nameless soldier / on an invisible border / Who manufactures? The cold-blooded gun / that caresses the hands of children / Who decides? Right or wrong / with a grandiloquent tone / everyone is searching for that someone.”

This multifaceted poet, who appeared to be aware of worldly affairs yet distanced himself from the noise, chose to influence ordinary people with similar sentiments through gentleness and sincerity. In his youth, he enjoyed depicting starry skies, trees, and small birds, expressing a keen interest in the vast sky and dreaming of a life flying around the world. In his later years, despite physical limitations, he remained passionate about watching drones and hot air balloons quietly soaring in the sky, imagining himself rising into the clouds. He lived sincerely and joyfully in this world, teaching people how to pursue love, beauty, and freedom. This zest for life echoes in a poem he wrote over sixty years ago, “The End of Spring”: “First, go sleep, / little birds / I have enjoyed being alive.”