Can Players with Lifetime Football Bans Teach Children?

In September of this year, the National Sports Administration and the Ministry of Public Security jointly held a press conference in Dalian to address the issues of match-fixing, gambling, and other corrupt practices in professional football leagues in China.

During this conference, the Chinese Football Association (CFA) announced that, based on the CFA Disciplinary Code, 43 individuals, including Jin Jingdao, received lifetime bans from engaging in any football-related activities in China (hereinafter referred to as “lifetime bans”).

Recently, it has been reported that the CFA will soon release a second batch of punitive measures. However, fans have pointed out that some players who received lifetime bans are now coaching at youth training clubs, with their names prominently featured in recruitment announcements.

This has led to confusion among fans, with one expressing to China News Weekly: “Does that lifetime ban mean anything at all?”

Doubts Among Parents Regarding Banned Coaches

Recently, Mr. Zou decided to leave his life in Beijing and return to his hometown of Dalian with his family. Before leaving, he began looking into local football training clubs for his son, who has a passion for football and serves as a goalkeeper in his class.

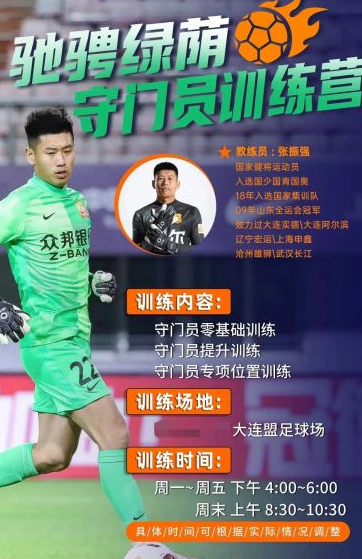

Mr. Zou expressed his concerns to China News Weekly, stating that he was particularly attentive to clubs that could offer qualified goalkeeper training. Last month, he came across a recruitment announcement on the official social media account of Dalian Meng Football Club for a goalkeeper training camp, where the coach, Zhang Zhenqiang, was described as a national athlete with extensive experience in various professional clubs.

Initially, Mr. Zou felt excited about the prospect of having his son trained by a former national player. However, he soon discovered that Zhang Zhenqiang was on the first list of banned individuals published by the CFA in September, with a lifetime ban due to serious violations of sports ethics.

The CFA’s announcement detailed that Zhang engaged in improper transactions and manipulated football matches for personal gain, leading to severe social consequences. Mr. Zou then questioned the legitimacy of Dalian Meng Football Club and sought clarification from local sports authorities, only to find out that the club was not affiliated with the Dalian Football Association.

The Limitations of the CFA’s Ban

The 2024 CFA Disciplinary Code offers a clear definition of the lifetime ban, emphasizing that it prohibits individuals from engaging in any football-related activities, including investment, management, and competition.

From a layperson’s perspective, Zhang’s involvement in coaching at a football club seems to directly contravene the ban. Legal experts, such as Ding Tao from Guangdong Zhuojian Law Firm, pointed out that the CFA’s bans are only enforceable within its jurisdiction. Since Dalian Meng Football Club is not affiliated with the CFA, the ban is ineffective in preventing Zhang from coaching there.

Thus, while the CFA can issue disciplinary actions, its power does not extend to regulating clubs outside its membership, which raises concerns regarding the enforcement of integrity in the football community.

Reemployment of Banned Players: A Debate

Retired Chinese football players often face limited career options after their playing days. Transitioning into roles within youth training or social media is increasingly common for former athletes. Some fans argue that players who made mistakes under duress—such as dealing with unpaid wages—deserve a second chance to contribute positively to youth development.

Conversely, others believe that allowing players with a history of misconduct to continue working in football undermines the CFA’s authority and diminishes the deterrent effect of its disciplinary measures. A director of a Beijing-based football training organization expressed concern that if banned players participate in reputable youth events, it could tarnish the image of those events, despite not being illegal.

In the current landscape, youth football clubs often operate under informal employment arrangements, making it relatively easy for banned players to work without formal contracts. As Ding Tao noted, since many clubs employ a flexible workforce, it complicates the accountability of banned individuals.

The CFA’s recent enforcement actions have faced challenges, with 13 individuals appealing against their bans. However, the CFA disciplinary committee upheld the decisions, further indicating the complexities involved in regulating player conduct.

Conclusion

The ongoing discourse around the participation of banned players in youth football coaching raises significant ethical questions. While the need for experienced coaches is critical in youth development, the integrity of the sport must be maintained. Finding a balance between rehabilitation and accountability is essential for the future of football in China. The situation underscores the necessity for stronger regulatory frameworks that extend beyond the internal governance of football associations to ensure a fair and ethical sporting environment for all.